Welcome to

Saint Michael & All Angels

Episcopal Church

2304 Periwinkle Way

Sanibel Island, Florida

Saturday Service 5:00pm

social hour to follow

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sunday Services

8:00 am &

10:30 am*

coffee hour to follow

(*will be livestreamed)

Wherever you are in life, there’s a place for you at St. Michael’s. We believe every person is created in the image of our loving God; that God's radically inclusive love excludes no one. Everyone is welcome here without exception.

We encourage you to explore our website, and join us for worship in person or online.

Email Fr. Bill if you have questions or simply stop by for a chat. Whatever method or frequency you choose to join us, you will always experience the warmth and welcoming that is the core of St. Michael's.

Spiritual Pathways

Practices for Embracing the Journey

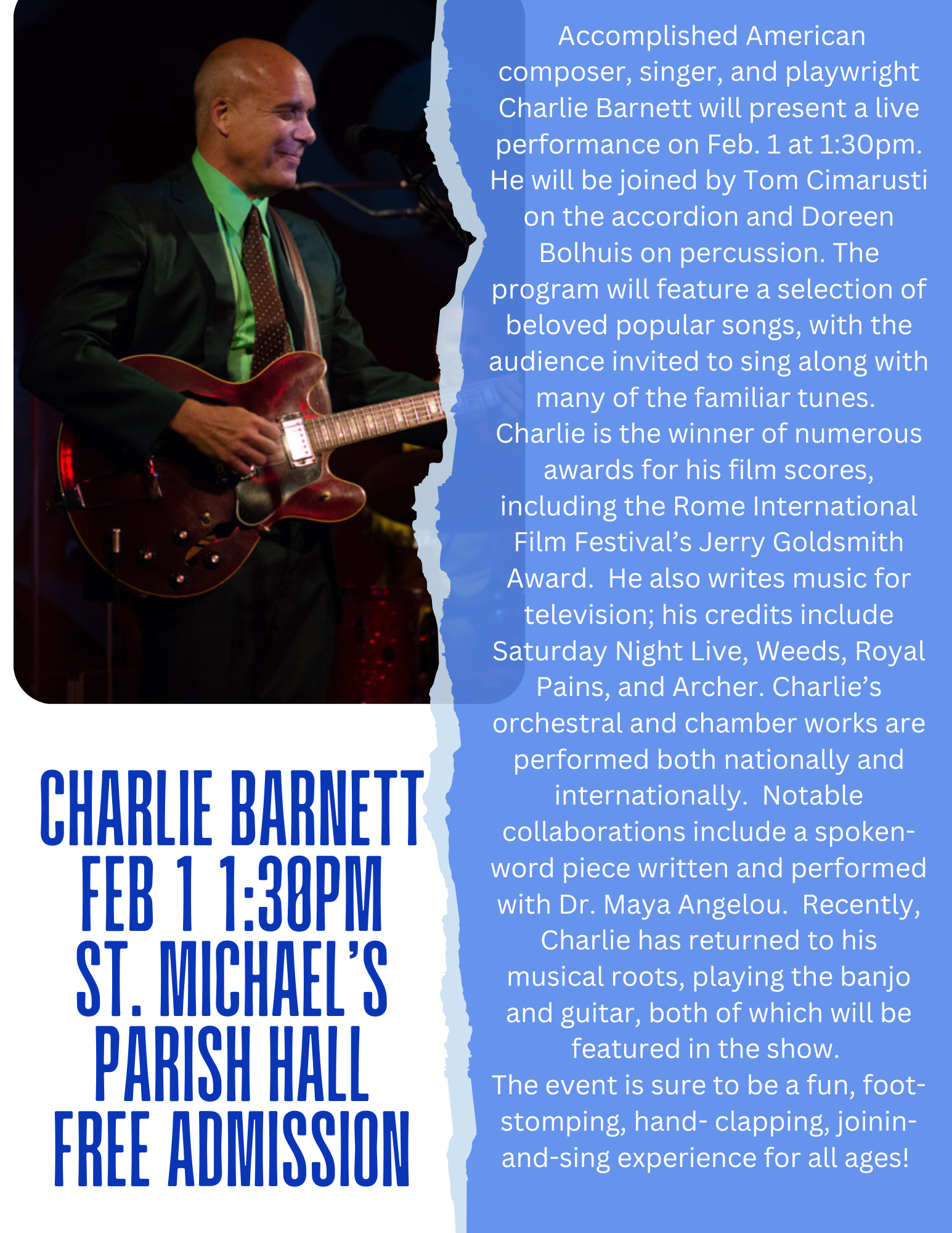

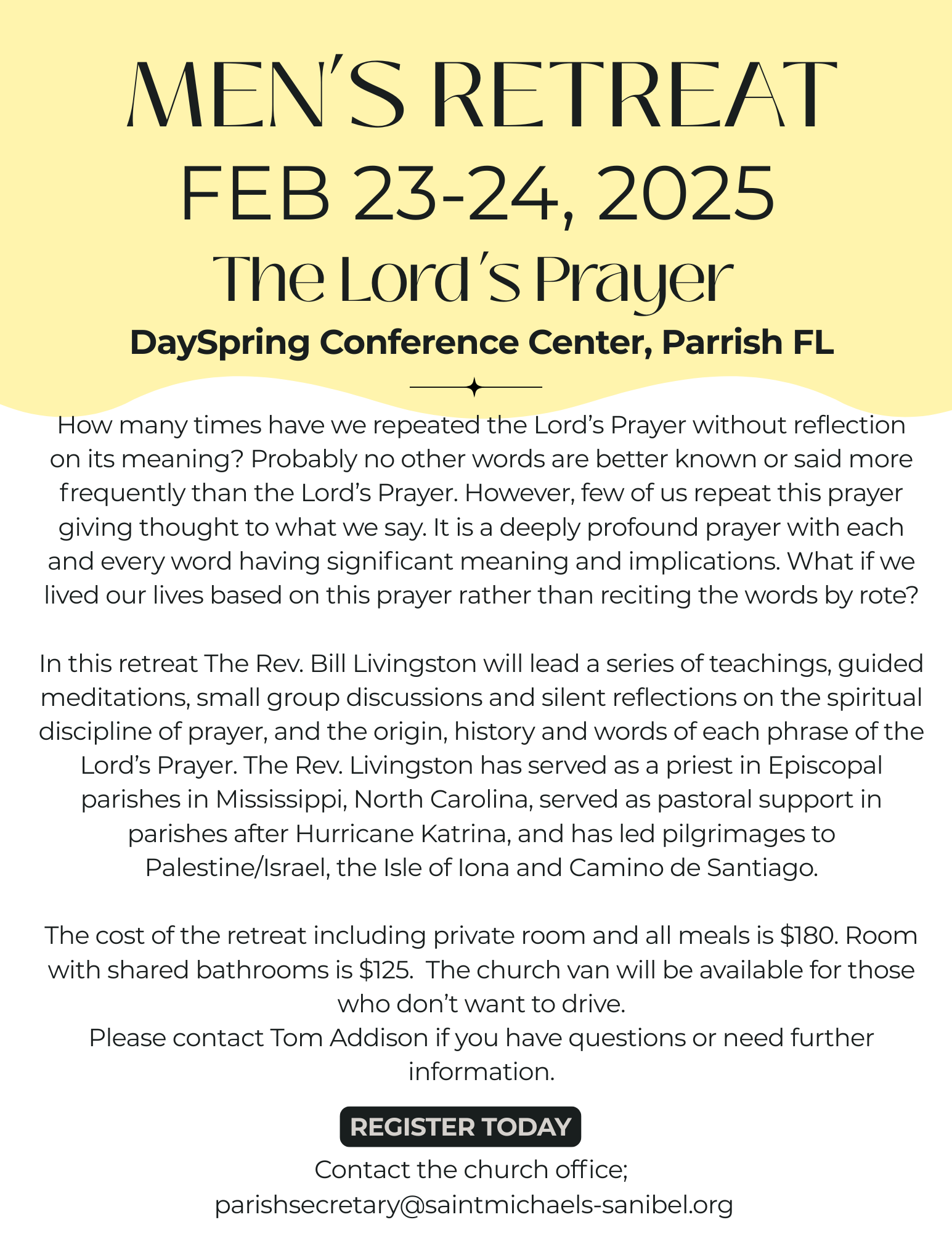

Upcoming Events

What to Expect

"The Episcopal Church Welcomes you", and we mean it at St. Michael's; whether you're just visiting the island or searching for a community that will embrace you as you are.

Get Connected

Stay in the know; sign up below to receive updates from Saint Michael's:

I'd like to receive the Saint Michael's Newsletter:

Recurring Zoom Events

List of Services

-

Thursday Bible Study with the RectorList Item 2

Every Thursday at 10:00 a.m. Meeting by ZOOM . Bible study with the Rector is a lectionary-based Bible study, held every Thursday, using the scripture readings for the coming weekend.

-

Thursday Night Prayer Service

Everyone is welcome to our Thursday Evening Prayer Service. In the Episcopal Church this is called “Compline", or "Night Prayer". It is a small, quiet serve of prayers at the end of the day.

Thursdays, 6 p.m. on Zoom

Phone-in (no video): 1-646-931-3860

Enter Meeting ID: 835 8757 2066

-

Monthly Men's Fellowship

Hybrid Men's Fellowship meet via Zoom and in person @ St. Michaels, Sanibel.

Check the Friday Brief each week for meeting dates and times.

28

Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Closed

8am Worship Service

10:30am Worship Service

Show all

29

Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Closed

30

Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Closed

1:30pm No Staff Meeting

31

Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Closed

New Year's Eve (Church Office Closed)

10am F.I.S.H. of SanCap - Counseling

11:30am Cancelled: Service of Holy Eucharist

2:15pm Cancelled: "Love First" After School Program

Show all

1

Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Closed

New Year's Day (Church Office Closed/no mail)

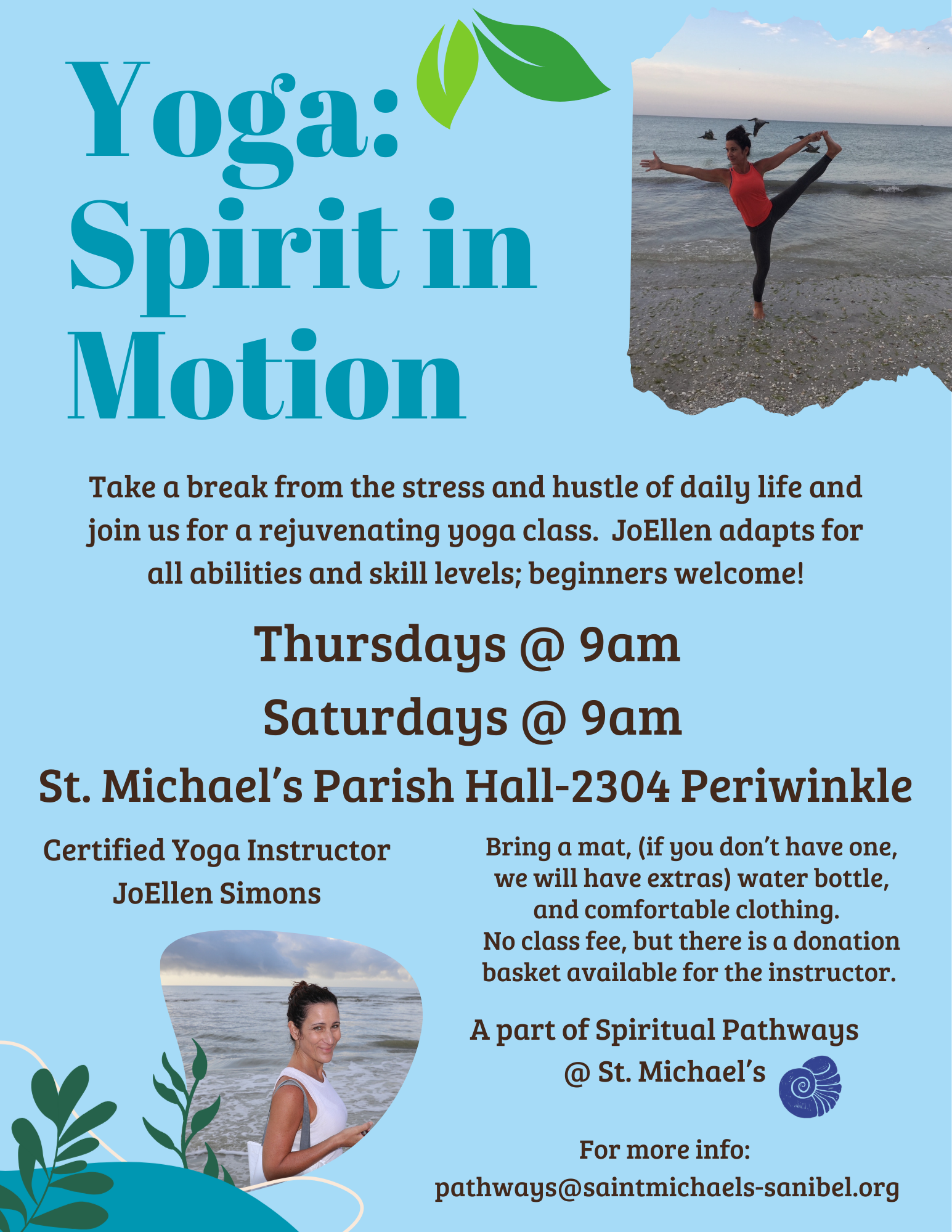

9am Cancelled - Yoga Class

10am Cancelled: Bible Study

1pm Santiva Islanders Community Activity - Bridge

1pm ZOOM: Digital Ministry

6pm Cancelled: Evening Prayer (Compline)

Show all

2

Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Closed

10am Grief Support Group - "Beyond the Broken Heart"

7:30pm AA Meeting

Show all

3

9am Yoga Class

10am Noah's Ark Thrift Shop - Open (

5pm Worship Service

Show all

4

8am Worship Service

10:30am Worship Service

5

9am CCMI EveryDay Cafe Volunteer Day

6

1:30pm Staff Meeting

7

8am ZONTA

10am F.I.S.H. of SanCap - Counseling

11:30am Service of Holy Eucharist

2:15pm "Love First" After School Program

Show all

8

9am Yoga Class

10am ZOOM: Bible Study

1pm Santiva Islanders Community Activity - Bridge

1pm Hybrid: Outreach Ministry

6pm Evening Prayer (Compline)

Show all

9

Volunteer Day at Misión Peniel

10am Grief Support Group - "Beyond the Broken Heart"

7:30pm AA Meeting

Show all

10

9am Island Woods HOA

9am Yoga Class

11am Overflow (Rear) Parking for City Hall Time Capsule Reinstallation

5pm Worship Service

Show all

11

8am Worship Service

10:30am Worship Service

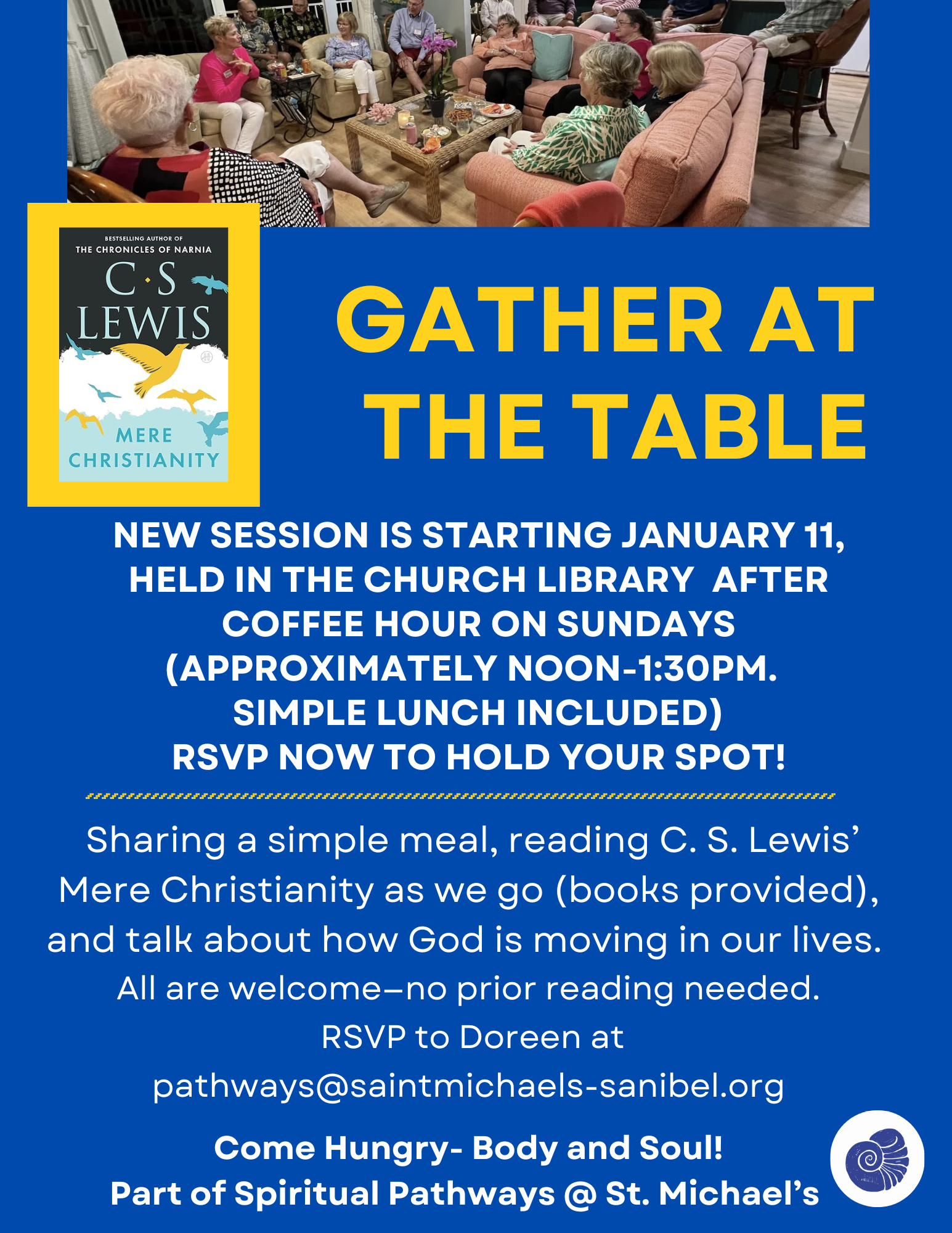

12pm Gather Round the Table

5pm Messy Church

Show all

12

11am ECW Board Meeting

12:15pm Women's Fellowship

3pm Spiritual Growth: Later Life Reflection Group

5:30pm FISH Workshop: Budget (part 1)

Show all

13

8:30am HYBRID: Men's Fellowship

1:30pm Staff Meeting

5pm Neighborhood Gathering (SP)

Show all

14

8:30am Community Engagement

10am ZOOM: Pastoral Care Ministry

10am F.I.S.H. of SanCap - Counseling

11:30am Service of Holy Eucharist

2:15pm "Love First" After School Program

Show all

15

9am Yoga Class

10am ZOOM: Bible Study

1pm Santiva Islanders Community Activity - Bridge

1pm Vestry Meeting

5pm Neighborhood Gathering (FMY)

6pm Evening Prayer (Compline)

Show all

16

10am Grief Support Group - "Beyond the Broken Heart"

7:30pm AA Meeting

17

9am Yoga Class

5pm Worship Service

18

8am Worship Service

10:30am Worship Service

12pm Gather Round the Table

Show all

19

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (Church Office Closed/no mail)

11am ZOOM: Christian Formation Ministry

20

1:30pm Staff Meeting

5pm Neighborhood Gathering (SP)

21

8am ZONTA

10am Spiritual Pathways

10am Interfaith Book Study

10am F.I.S.H. of SanCap - Counseling

11:30am Service of Holy Eucharist

2:15pm "Love First" After School Program

Show all

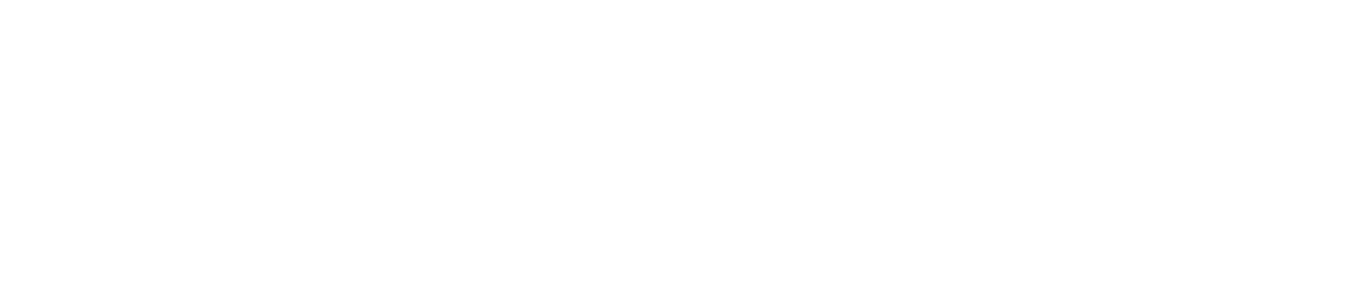

22

9am Yoga Class

10am ZOOM: Bible Study

10:45am F.I.S.H. Workshop: Frauds, Scams & Identity Theft

1pm Santiva Islanders Community Activity - Bridge

5pm Neighborhood Gathering (FMY)

6pm Evening Prayer (Compline)

Show all

23

2026 Parish Retreat

10am Grief Support Group - "Beyond the Broken Heart"

7:30pm AA Meeting

Show all

24

9am Cancelled: Yoga Class

5pm Worship Service

25

8am Worship Service

10:30am Worship Service

12pm Gather Round the Table

Show all

26

9am CPR/AED Training

5:30pm FISH Workshop: Budget (part 2)

27

8:30am HYBRID: Men's Fellowship

1:30pm Staff Meeting

5pm Neighborhood Gathering (Snb)

Show all

28

8am Cfi leadership

10am Interfaith Book Study

10am F.I.S.H. of SanCap - Counseling

11:30am Service of Holy Eucharist

2:15pm "Love First" After School Program

Show all

29

9am Yoga Class

10am ZOOM: Bible Study

1pm Santiva Islanders Community Activity - Bridge

5pm Neighborhood Gathering (Snb)

6pm Evening Prayer (Compline)

Show all

30

9am Dress Rehearsal

10am Grief Support Group - "Beyond the Broken Heart"

7:30pm AA Meeting

Show all

31

9am Yoga Class

11am Memorial Service for Lee A. Almas

5pm Worship Service

Show all